"Only the medium can make an event" - Baudrillard

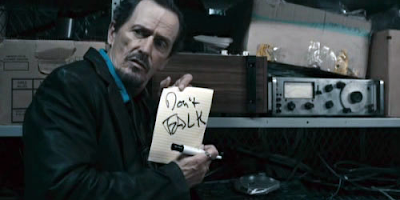

In PONTYPOOL the world ends not with a bang but with the words "in Pontypool the world ends not with a bang but with the words 'in Pontypool the world ends' in Pontypool a ever-tightening stutter-stop loop that causes cannibalism. It is spoken, and having spake, the words lead spaken to death, unless they're in French. No time to be running an early morning English speaking radio talk show, as emergency broadcasts (or pirate interceptions, in French so who can tell?) and mass confusion envelop you and your crew, especially not in the early hours of the morning on a typically white winter of a a middle-of-nowhere Ontario town (the title). But there they are: early morning DJ Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie), a self-styled outlaw with a yen for conspiracy theory; his harried but maternal line producer, Sydney Briar (Lisa Houle); and cute blank of an intern Laurel-Ann (Georgina Reilly), and a lot of voices calling in to deliver astonishing reports that go blank in big flurries of horrible chaos as people chant meaningless phrases over and over then each other.

The stories sound like the ravings of the town's many drunkard fishermen and it's not until BBCI phones that Mazzy realizes his town has become the news; what was mere minutes ago a punishment assignment (Pontypool the Canadian equivalent of Siberia due to his cantankerous airwave anarchy) becomes a matter of being too spooked to make his Wolf Blitzer mark. These three people at the station are the only ones we see for quite awhile, and they haven't seen any of the things described and they are hard to believe in a town where nothing ever happens, or even if anything did. All Mazzy and Sydney and Laurel-Ann have are the callers, and all other lines--police radio, AP wire, 911--are dead, or dying, just static and then the alien-like buzzing we belatedly recognize as the emergency broadcast signal. It's like the whole world has shrunk around their little studio --they're an island in an already island-like town. Pontypool, where they know most of the residents by name, winters stretch forever in a haze of booze, depression, and shuffling from heated car to basement to home, with windows just reflecting an opaque wall of darkness and snow.

What really makes it work is the power of imagination coupled to the frustration of never getting the complete story --we strain at the bits of the movie's limited known, and we recall the way breaking news drips slowly with newly emerging facts buried in an avalanche of idle speculation to fill in the minutes. There was a time when 'showing' mass cannibal carnage in all its Tom Savini-ish Fangoria glory was a subversive act, something to look away from in blanched shock; now it's the opposite --showing us almost nothing becomes a new form of subversion.. There are still countless zombie / mass plague insanity knock-offs and for a few seconds the 'found video footage' trick was novel but that was 10 years ago, now only Pontypool (2008) finds an original tack, sailing towards the source of the original Romero film's hidden candy shell power, the news broadcasts, the way the professional newscasters with their cigarettes and thick glasses and bustling assistants behind them all both offer reassurance and terror, their steady cool and news voices only serving to make the pronouncements about 'packs of ghouls' more terrifying. Pontypool rocks that same tack. It's almost too post-structuralist for its own good at times but makes terrific use of uncertainty--are these reports just drunk ice fishermen spinning yarns?--and delves deep into the way imperiled people instinctively turn to the media to provide a narrative structure for the chaos around them, and even the media finds itself compelled to provide one. Without clear visuals, long shots of the calamity, official press conferences, the calm but thrilled voice of an reporter standing in the snow near a firetruck, we have only our own imaginations with which to structure things. At such times radio can reach the deepest vaults of our mind, forming deep cerebral cortex responses not normally our own. I first heard of 9-11 on a radio at work, for example, hearing Peter Jennings describe the towers falling and planes crashing into Washington, I imagined the world consumed in fire, civilization ending all around us -- when I finally saw the footage, horrifying as it was, it was almost a relief.

But that's it - we can't always be near a TV with CNN, but even if the power goes out we can find and old battery-operated radio. We all secretly love calamities (as long as they don't happen to us) because suddenly, for once, something is happening and the mood amongst the reporters is always jubilant --careers are made in such moments, ala Wolf Blitzer during the Gulf War--and for once no one can predict what will happen. The whole world seems to wake up in such moments, to be unified in their collective shock and awe, secretly loving the thrill of orbiting closer and closer to a possible armageddon.

What really makes Pontypool a delight beyond this gimmick is the comfortable sense of being in a warm radio booth on a frozen Ontario small town morning, and the early stretches of incoming news as DJ --- begins to think people are all fucking with him -- so organic it all unfolds in more or less real time for long stretches without the viewer (me at least) noticing; as the influx of news and shaky narration causes a breakdown in our perception of reality. In other words while not being specifically scary, and always kind of funny, there's a sense that something meta is always at stake, something that might leak out and effect even your blogging about it.

The news' secret agenda has always been to cast anxieties about the prevailing social structure's solidity off on handy targets: crooks, shady pols, terrorists, which then makes the news a comfort - you see which way the finger of blame points, and you make sure you're standing behind instead of in front of it. So when the TV station reports on a mass insanity uprising, it becomes 'real' in a way it couldn't be otherwise and in the process strengthens the illusion of law and order's ultimate omnipotence. As Jack Torrance would say, cannibalism is okay to talk about in front of their son, because he "saw it on television." It's the same for us. In fact cannibalism's main problem in Pontypool lies in its invisibility. Thus one Romero news broadcast is worth three dozen CGI zombie army ant hill urban killing floors in less interesting but bigger budgeted films. The end of the world can't be accepted as a legitimate event until it is authenticated through the TV. Unless the revolution is televised it cannot exist. This is what Baudrillard and McLuhan can teach Gil Scott Heron.

In Dawn of the Dead (above) Romero yanks even that little buoy of illusory 'objective reality' away; the TV station itself starts to collapse from nervous exhaustion, devolving into petty arguments and agendas. Those who haven't had a chance to experience directly see the looming chaos, such as the black intellectual in the final news show, commandeer the zombie outbreak to suit their agenda, labeling it as a cover-up for cop violence in the ghetto. The opening events all take place at the crumbling Philadelphia local TV station, ending with the producer escaping with her helicopter pilot boyfriend and two SWAT guys. When they're later able to find a TV, there's just one continuous talk show left, with two pundits yammering in a progressively more hostile, childish manner. Reality, civilization, has in effect become totally subjective. It was like that once, maybe, before cross country railroads and telegraphs. But each man was connected to some tribe, some family in those days. Now our tribe is purely virtual, friends from everywhere except our own neighborhoods.

In Dawn of the Dead (above) Romero yanks even that little buoy of illusory 'objective reality' away; the TV station itself starts to collapse from nervous exhaustion, devolving into petty arguments and agendas. Those who haven't had a chance to experience directly see the looming chaos, such as the black intellectual in the final news show, commandeer the zombie outbreak to suit their agenda, labeling it as a cover-up for cop violence in the ghetto. The opening events all take place at the crumbling Philadelphia local TV station, ending with the producer escaping with her helicopter pilot boyfriend and two SWAT guys. When they're later able to find a TV, there's just one continuous talk show left, with two pundits yammering in a progressively more hostile, childish manner. Reality, civilization, has in effect become totally subjective. It was like that once, maybe, before cross country railroads and telegraphs. But each man was connected to some tribe, some family in those days. Now our tribe is purely virtual, friends from everywhere except our own neighborhoods.

Pontypool zeroes in on this issue by presenting the entire 'event' from within a radio station on a single day. It is only Mazzy and his producer who can determine to what an extent they should continue to connect their listeners to their callers. In this town we learn the 'eye in the sky' for local morning traffic is an old dude with binoculars on the hill, playing chopper sound effects so we get the impression he is in a helicopter, which for some reason makes us feel warm, loved, guided into work by a heavenly hand. A weird musical family shows up dressed as Arabs to sing bizarre but hopelessly square 'Arabian' songs, the dad firing a plastic Uzi for accent (I had the exact same one as a kid). This isn't given much commentary in the film but it's a good metatextual meltdown signpost. We learn that the Pontypool crisis involves the repetition of phrases until they become meaningless, a weird infection of thinking transmitted through language, an idea that rewards deep contemplation if you approach it with enough McLuhan, whose concept of language as "a form of organized stutter" underwrites the film's post-structuralist collapse, where meaning and syntax become derailed, causing human brains to go crashing into the morass of subjective looping, where each new repetition increases in violence until they rend one another limb from limb. Is this something to do with Quebec separatist intellectual terrorists? The French language seems suspiciously immune.

While the chants of the crazies may seem meaningless, what we glean from Pontypool is that everything has meaning, and the power of chant is no fluke. Anyone can use repetition to either make themselves calm (the rosary, chanting) or drive themselves crazy (All work and no play make Jack a dull boy, sections of Mingus' Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, chanting) or both (dervishes, chanting). What makes Mazzy interesting as a character is that he is aware of this power, and does not take his DJ power lightly; even his school cancelation snow day news carries poetic, grim observations, and he predicts the coming crisis all based on one odd morning encounter, even knowing he may be starting the very fire he's railing against by railing against it. And he gives both women cute innocuous valentine's day cards, indicating that beneath his gruff exterior and contrarian shock jock tactics (mild compared to America's) beats the heart of a regular sentimental guy, a Canadian in other words, a bit of a rotgut and cigarettes innocent. In other words, this is not an American film. There's no in-fighting, cursing tantrums, misogyny, lectures, or grandstanding. Sydney's anxiety over what her DJ's going to say is moderated and modulated moment to moment as he pushes the envelope but then eases back; her riding him to be less incendiary but tempered by an almost motherly need to keep him feeling grounded, trying to encourage Laurel-Ann to feed him the news slowly and get confirmation first so he doesn't start a panic.

This is perhaps the film's key concept and also perhaps its one dubious theme, the conception of language as a virus, that it's not the news driving us crazy burt the saying that the news is driving us crazy which is driving us crazy, which is very Cronenbergian, making us wonder if his themes are somehow as much related to Canada itself as to his own clinical doctor experience. The movie seen on streaming (on Netflix) masterfully sets itself up as a virus via the internet, through which there are no coincidences in whatever you happen to be doing as a passive viewer. The media breakdown can extend to your life -- is there a virus within Pontypool itself, that scrambles the very particles of code within its signal? Or was my girlfriend, in the throes of a phone interview with some comedian in the other room, tripping on the extension cord for the WiFi, causing the Netflix stream, as well as internet, to go out in a single flash right at a key moment in the film? It was so perfectly timed I became as unnerved as old Mazzy. Let's pause and ruminate on what version of the new 3-D that will be, when the film makes your TV explode at a key plot juncture.

Sure that's a sick idea, but that's the thing -- when the news envelops you then you don't really know what the hell is going on; you don't know what is real because you can't see it so your imagination fills it all in and does a much more apocalyptic job of things. You need electrical power, devices, connections, reports, and images from far enough away that you can see what's been destroyed and what hasn't. None of that is possible without a vantage point from far enough away. Because there's one thing that can reach even the deepest of burrowing loners and isolationists, the media, the radio waves, thought, sound, speech. Pontypool's climactic moment of interdimensional communication is when emergency broadcast interruption comes roaring through the station, cutting out the broadcast to announce those listening should refrain from speaking, using terms of endearment or embracing loved ones, or using the English language, ending with "don't translate these words" which Mazzy reads, translated, over the air waves- Is this, then, a structuralist terrorist attack. Oh yes Quebec resistance, how very French of you!

|

| Top: Lisa Houle - Pontypool / Bottom: Anna Karina - Alphaville |

|

0 коментарі:

Дописати коментар