Valentines Day means red hearts and flowers, dinners by candlelight, hands reaching across the table. Like this dubious 'holiday,' horror films are defined by their cliches: damsels in nightgowns holding chandeliers; undead hands reaching from a mound of dirt to touch your heart; stock footage full moons hitting your eye, like our love, baby; frightened horses..."easy... steady... steady, girl." Such a well trod path ensures we don't get lost. It's as easy as falling off a bike into the abyss.

But if you are an African American artist making a 'black' horror film, your cliche palette is doubly restricted: blaxpectations are always high, and then low, the split between a disciplined soldier of community betterment and a louche parasite: for every rainbow-feathered pimp you need a monologue about brothers being kept down by the man; for every jive-talking freak you need a noble cop fighting white corruption. It's got to be funky, but brother, it's got to be cognizant of its social message.

In addition to V-Day, February is Black History Month, a time when the message runs rampant, diluted by 'safe' social commentary that beg the questions: Can the black experience be represented in a risky, artistic, even abstracted manner? Or must 'intelligent' blackness be rendered only as noble suffering, dignified non-threatening mouthpieces for equality.

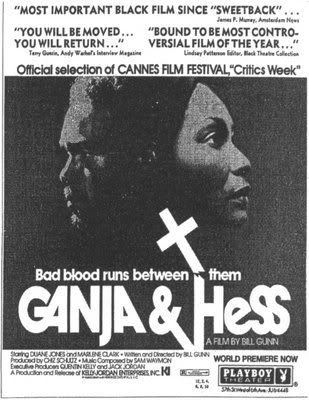

African American playwright/actor Bill Gunn was given money to make a black horror film. AIP's BLACULA (1972) made bank. And it was made by a white man. Get a brother to make the next one, some suits thought, maybe things will get even bankier

Gunn gave them something far different than a FUBU-LACULA. GANJA AND HESS wasn't blaxploitation at all, but Gunn's own thing, a nouvelle vague semi-experimental horror love story that was both a choppy, fragmented mess and inescapably mesmerizing. GANJA AND HESS looks haphazardly framed, grainy, amateurishly recorded, but once you adjust your eyes and ears, poetry blooms.

Not least of its assets are two evolved and interesting black characters: the rich, isolated doctor Hess (Duane Jones) and his future wife, Ganja (Marlene Clark), a very unusual type of strong black woman who manages to assert herself without rustling feathers or being bitchy or unsexy. They are antithetical and ambivalent as in the best tragic figures of Shakespeare -- like Macbeth and his Lady. They have the guts to admit they don't really care if other people die. They are characters dealing with blackness, as opposed to being representations of a blackness toned down or played up to fit pre-fabricated molds (see my 2007 analysis of this via Cabin in the Sky, here).

I love Nick Pinkerton's description from the Village Voice doing a Bill Gunn retrospective:

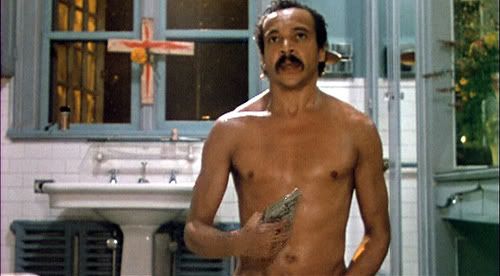

Hired to crank out a Blacula knock-off (with a drug-joke title), Gunn instead wrote a surreal love triangle among black sophisticates, devoid of sex-machine phoniness, and directed it in a muttered, disorienting style, with a strange brew of Afro-Euro symbolism. Duane Jones is Dr. Hess, a gentleman scholar studying a pre-Christian African blood cult; Stop's gorgeous, sloe-eyed Marlene Clark is Ganja, as lively and droll as Hess is lethargic. Gunn himself plays the turbulent artist who infects the doctor. He had a genius for writing monologues, and delivers them with absorbing intensity, especially in his character's schizo suicide dream of playing both murderer and victim, showing Gunn's fascination with the divided self.When seeking a way to wrap your narrative-expectations around Gunn's "muttered, disorienting style," it helps to have a bit of a grasp of black cinema history. The films, for example, of African American pioneer filmmaker Oscar Micheux were notoriously mismatched and fragmented, as if the audience was handed a stack of coupons, leaflets, half-finished letters and told to read through them and let the complete novel form in their brains. For sure, there's a feeling, as in the best art, that your own brain is the final editing room for the film, with the series of seemingly disconnected scenes (are whole pages of exposition and explanation in GANJA missing?) coming together in your mind as you watch it, creating a delayed sink pull drag effect, as if by the time you figure out something's after you, it's got you by the neck and you're already dead.

George Romero showed a remarkably colorblind casting ability with Duane Jones in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) and it's perhaps no coincidence that Jones plays the lead in GANJA AND HESS. Like his character in DEAD, Jones' Hess is a man with no time or interest in proving his intelligence or lessening his powerful image to not intimidate whitey. We see his intellectual strength, fatherly tenderness and icy reserve, for example, when he visits his son at boarding school, and the pair have conversation in French, a reminder of the way so many black artists expatriated to Paris in order to escape racism. He's closed-off, aloof, abstracted.

Examples of the racism a character like Hess would have to endure were all over the papers when GANJA AND HESS opened, and when it was selected to represent America in the 1973 Cannes Critic's week. Gunn wrote this in a letter to the NY Times on May 13, 1973 (following the tepid reviews of his film, including outright admissions by critics of walking out):

Indeed one wonders, would this film be recognized even today? Probably even less so now that our culture has grown further distracted by CGI and MTV whiplash editing. GANJA does drag a bit in the beginning, and I confess I spent the first ten minutes kind of puttering around the TV, distracted. The film stock is grainy and the shots seem poorly framed and too long, but if you pay attention the film slowly and inexorably rewires you to a new sort of low budget film language. But would I have paid that much attention if I was a film critic seeing this in a screening room on a busy day of deadlines and headaches? Who knows, I might have dozed off. It certainly would have helped to have read a Cahiers du Cinema appreciation of it in advance."If I were white, I would probably be called "fresh and different." If I were European, "Ganja and Hess" might be that little film you must see." Because I am black, I do not even deserve the pride that one American feels for another when he discovers that a fellow countryman's film has been selected as the only American film to be shown during "Critic's Week" at the Cannes Film Festival, May, 1973. Not one white critic from any of the major American newspapers even mentioned it."

On the other hand, if the film was French, these Times critics would have fallen all over themselves trying to 'discover' it first. I often wonder what Godard movies would be like in France, without subtitles, as subtitles fit so well his post-structural imagery, and so much of his dialogue overlaps or is mixed low making full comprehension impossible without them. Gunn's film basically answers my question, and the answer is _____.

To appreciate this film you have to let go of having everything spelled out, you have to trust your unconscious understands the background whispering, the disjointed meanings, even as you scratch your head and think about doing the dishes. Stick with it, and your unconscious will reward you.

The main thing that kept me rooted to the film was the incredible electronically-warped soundtrack: African tribal chants and spirit calls echo throughout the film like an ancient tribe stumbled upon a flanger and a feedback amp and managed to send their chants forward through time. In Gunn's world, the distant past and the future are both relatively unfixed: the past can roar up to grab you and the future is already biting you and draining your blood so it can survive into another day. Gunn uses a growing feedback squall to indicate when the 'bloodlust' jones is on our vampire hero, making us aware of the link between vampirism and heroin addiction, or alcohol, the way a person who's been waiting for 4PM cocktail hour since he woke up will snap the head off a person who suggests going on a three-hour hike.

The droning demand for blood and the ghostly presence of African drum on the soundtrack make the ethereal score an audio-mimetic equivalent of the ghosts that haunt The Emperor Jones in Eugene O'Neill's play. An early suicide in the film is set to music that gradually echoes into abstract noise as the camera circles around the self-inflicted carnage, creating a dizzying POV sense of a soul suddenly freed of its body, no ears to turn the dissonant sound waves into music.

Is this surreal echoing booming what a tree sounds like if it falls in the woods and there's no one around to hear it? I got a panic attack when a similar effect was done on the song "I can't live (If living is without you)" in Roger Avery's RULES OF ATTRACTION. Watching this scene it was like that panic attack finally blow its own brains out, like a rose from the tip of the crown chakra. More than any other 'vampire' film, 'black' film, or even 'white' film, GANJA AND HESS dares to examine sound and vision that lie past life and death dichotomies, refusing even to see a difference. It re-imagines the Bluebeard legend as a chance for forgiveness and admission of true and refreshing ambivalence about life.

What's missing in the film is a serious line of continuity, and that's where Gunn relies on cliche, as we "know" the missing scenes (continuity shots are rare - whole chunks of the film seem to have been left out). Clearly, a mix of budget constraints and artistic control necessitated some of these choices, but they work, because they force us to fill in the blanks, like watching a foreign language film without subtitles. And then, when Ganja shows up, she's so warmly human and yet so strong that the film kicks into gear, as you've been straining to get into it through Duane Jones' thick distancing persona, you're sensitized and ready for her sensual assault. I wont spoil it, but about halfway through the film she delivers a long, tearful monologue, lit only by firelight, and the subsequent eruption of happiness and music is one of the most powerful cinematic moments I've had in awhile, and the long single take monologue in dark lighting is what helps catapult it. In short, Gunn uses his limitations for powerful effect, mixing the agonizing real-time emotional build-ups with ecstatic release: all the strain pays off.

Looking at this marvelous, truly unique film as a whole, it makes a fine mirror parable to problems discussed at the start of this essay: How can a black artist be true to himself, relevant to the pop cultural landscape, and supportive of his black ancestry all at the same time. And should a black artist be continually burdened with conveying the 'entire' black experience, or indeed any of it? Gunn also addresses this in his response to criticism in the Times:

This innate 'extra' requirement for black art is like a lead albatross affixed to every struggling black author or artist, and a problems faced by Hess in the film: knowing the only thing that can hurt him is the shadow of a cross over his heart, he decides to get born again down at the local church. Sometimes, merely climbing out of a swimming pool can be a true baptism, just like sometimes raggedy scraps of black film can come together to form jaw-dropping art, and sometimes that art can be recognized, even if it's made by a black man and is ignored by white critics in his own country, even if the black man is expressing himself rather than the all-consuming thirst of blackness."Another critic wrote - where is the race problem? If he looks closely, he will find it in his own review."

(Special thanks to poet/performance artist Tracie Morris for turning me onto this film and informing sections of this review. And thanks to The Temple of Schlock.' for posting that Times article, reprinted in part above. Check out!)

0 коментарі:

Дописати коментар